From the living room to the dance performance

At home, my old man played the piano well, so Beethoven played a lot. There were outstanding records of classical music, also of folklore, and well, obviously, when I was a child, all that music started to stick in my body. I would lock myself in the living room and start dancing, and that moment was so sacred to me that I didn’t want anyone to pass by. At home, they knew that if I was in the living room dancing, they had to turn around and go through another door because I would get angry if they interrupted me. The feeling of dancing was always powerful for me. So, one day, my mother bought a tulle and dancing shoes and took me to classes. There were only classical or Spanish academies in Concordia, and they sent me to classical. When I got to class and saw all the girls with their tulle holding the barre doing the same thing, I got angry and said that was not what I did, that for me, that was not dance. My mum got stuck with everything, with the tulle and shoes, because I didn’t want to go on.

Luckily, a girl, Lidia Santich (Lila), had studied contemporary dance, “Danza Moderna,” as it was called at the time, so that I could go to her classes, and then I started to play. I joined a municipal modern dance ballet with María Antonia Loroca a little later. And then, when I was nineteen, I came to Buenos Aires and studied for a year with a Russian, Wasil Tupin; in that class, there was the whole seedbed of the Colón. I followed my path with corporal expression; that is to say, I varied and mixed different things. That’s why I don’t consider myself a formal dancer, with the training that the Colón or the Taller del San Martín can give you. Different teachers taught me, and when I grew up, I studied corporal expression until I was halfway through. I consider myself more of a performer; I’m an improviser, and my thing is performance dance.

Back to dancing or the Under porteño

When I came to Buenos Aires, I was on the run. In 1975, they put a bomb on my house. I was seventeen years old, and that’s when I decided to leave Concordia. It took me a couple of years to do it: in 1977, I came to Buenos Aires to study dance. I also came escaping from the small-town thing because they pointed the finger at us; the parents didn’t want me to go to my classmates’ house. I was left without youth. In the middle, I had my two girls, and I was revived in the artistic and even youthful sense when I was thirty when I entered the Under, which revitalized me and gave me the power that had been taken away from me.

Around 1988, I couldn’t find my way back to work until I started dancing in Cemento, in the Parakultural, in Medio Mundo Varieté. I entered a strange world, which fascinated me, with Klaudia con K, Batato, Diego Biondo, many transvestites, and many performers. That was my re-entry into the world of dance. I was with the group, we had a movement in Babilonia, a club in Abasto, and street movements. In 1989, we made a film for the film school in Los Baños, Cuba, called “Bicicletas a la China.” They had entered a student march in Tiananmen with tanks and killed two hundred students. So political art organizations decided to make a move: they called for two hundred bicycles to come to the Obelisk, and from there, we left with a van in front in which Fernando Noy rode with his megaphone, and every so often that caravan would stop, and a performance would take place. I remember it was cold, and I was on the corner of Perú and Av. de Mayo waiting for them in my red tunic – I had a very Isadorian red tunic – and when the bicycles appeared on the corner, they threw themselves on the ground. I jumped up and down to dance without music. After that, the caravan went on. Those were my beginnings in art and politics. The Under and these kinds of street moves were my most potent artistic nourishment.

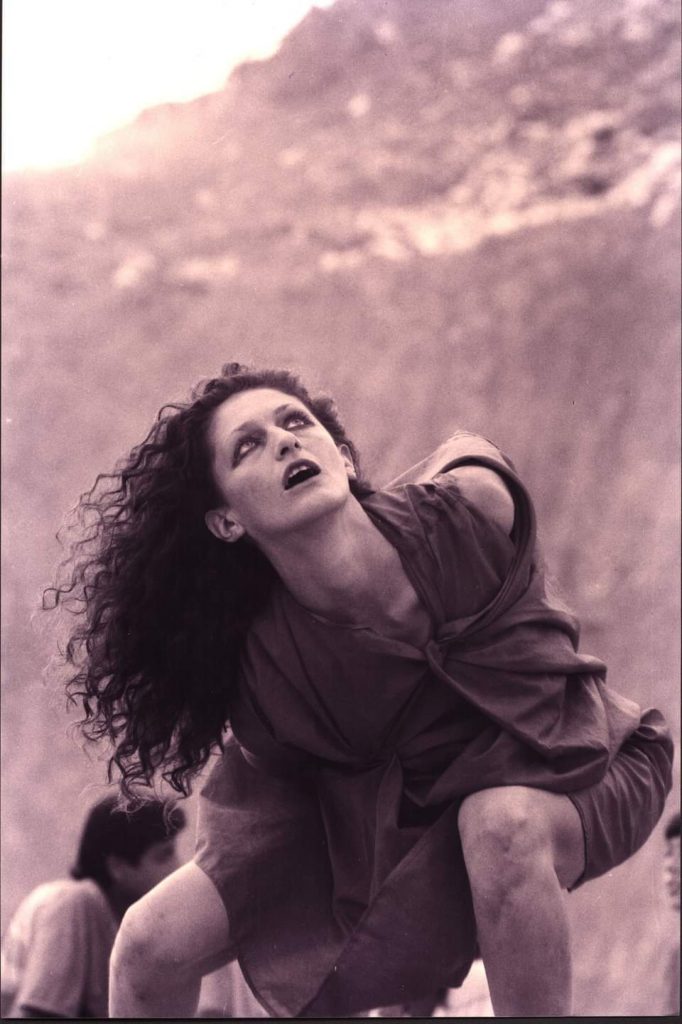

The Under was a counterculture. We were a band of people who generated something outside the official circuits; they were all basements or boliches (night clubs), a mixture of Rock and Roll with theatre and dance. I remember when I went to Medio Mundo Varieté, and I was attended by Leandro Rosati, an actor and director, who, together with Dalila, owned the place. He opened the little window with the iron door, and I said, “I am Blanca, and I dance.” I was so nervous that this came out: “I am Blanca, and I dance.” I mean, my name is Blanca; I’m not white. He opened the door, and I said, “Look, I want to come on Mondays.” on Mondays, Batato was the artistic director, and I said, “I want to come and dance, to do little improvisations.” He said, “Well, you come next Monday and watch, and the other Monday, you come and do it. If they throw you with something, you don’t come anymore, and if people like it, you come back”. “If they throw something at you,” people would participate to the point of saying, “Get out of here, you bastard.” So I bought a white nightgown at the American fairs, and that day, I went out and danced to “Les 40 Braves” by Irene Papas. I went out in the white tunic and had a catharsis because I had wanted to dance for a thousand years. I had danced on the stages of Concordia, but not like that with so many euphoric people at one or two in the morning. It was so powerful that I danced on the cement and hurt all my feet, but I only realized it the next day when I had to heal them. Because people howled, people shouted, and I remember that when I went in, Batato said, “But what’s going on out there? There’s so much racket”, and they shouted for me to come out again. So, from then on, I started going every Monday. The next day, I had to be at the bank. I was asleep, my daughters were small, and I had separated; it was a delirium to sort everything out.

Then I also met Omar Chabán, who called the artists to Cemento to express their opposition to the Gulf War, and I put on my black gauze nightgown, tied a scarf, and danced to Wagner’s “Love of Tristan and Isolde.” There were hundreds of people; running around on that stage was excellent. And when I came down, Omar hugged me and said, “Who are you.” That’s how I got into the places. At the Parakultural, the same thing happened to me. I started to run around to dance, and Batato and Urdapilleta approached me; it was like an impulse that took me to the places I liked.

Teaching: expression and improvisation

For many years, I felt very insecure in front of the dancers because I didn’t know any particular technique well. I had done a bit of everything, but I wasn’t a specialist in one dance technique and felt insecure once I could assume that my specialty was the tools of improvisation and composition, that little box that can be enlarged, shrunk, reinvented. So I lost my fear of dancers and said, “Ah, here’s something else we can get into.” So, I dedicated myself to studying and teaching those tools; I specialized in gathering everything I thought could open a more personal world, Pandora’s Box. They are tools that are easy to get into but mighty; when you do that, you find your power.

At UNA, I did the Perf Solo Workshop once a week for two hours, and we made the most of it. The students suddenly found themselves with their creations. They couldn’t believe it because, in general, you are very dependent on being directed, on others having good ideas, on the fact that you are always learning, and on the fact that the teacher is the one who knows. When I read Ranciére’s The Ignorant Teacher, I understood that the teacher can be a hindrance because the student thinks that they have to reach something that the teacher has, which blocks one’s creativity and power. So the teacher has to leave that place, move away as much as possible, and let the student confront himself with his power. With the tools of improvisation, anyone can produce an exciting dance. You give them the tools, and even if they don’t have the virtuosity of a dancer, they can create something exciting, even scenically speaking.

I was at the Instituto del teatro Avellaneda, at the Escuela Metropolitana de Arte Dramático and at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes. All this happened from the age of forty because, at thirty-nine, I studied corporal expression; that is to say, I began to memorize something. That’s when I started to get into places because of my curriculum; I was still half Under, but I managed to get into institutions, and for me, it was a lot of fun because they paid me to do something I liked. I couldn’t believe it. As a choreographer and as a dancer, I never earned a peso, and I don’t make an apotheosis of this; on the contrary, it seems to me that there is a lack of public policies, that people have to be paid, that choreographers have to be supported.

Feminism, public space, political performance

Large spaces fascinate me. Something opens up inside me when I see one – a giant room or a landscape. It’s that thing of being a child of the river, of the big spaces, of the beach, of being able to be in contact with distances; something fascinating for me. Later, I began to find a much more political twist to those open spaces, especially when I began to work with trafficking. Let’s say that it went from a child’s game taken to adulthood to an awareness of the political, to “we have to win the public space”; people must know about it— a mixture of sensations and emotions crossed over into art and politics.

In 2008, feminism was already making a lot of noise to me. Above all, seeing that the girls who disappeared for prostitution were nowhere to be found and only a few people were talking about them. When something makes noise to me, I have the mechanism of putting my body into it. I don’t even understand what I want, but I put my body into it to heal, to say to the world, “Hey, this is happening.” For me, putting the body is more accessible than saying it. The thing is that Erica Colef, who was studying directing at the UNA, set up the “Cuerpos en venta” movement at the Inter-American Women’s Forum and asked me if I wanted to participate. I told her I was going to participate in the issue of trafficking. I told her I would be doing some things with a colleague, and there would be some drums, and everything would happen when the women at the Forum went out into the internal hall of the Law School. I bought a black net dress, like a wedding dress, which left me naked – there was nothing underneath – I pinned some big bar codes to it and covered my face with a tulle. I summoned my students and told them to approach me, very slowly, with some cardboard with talcum powder on it, and then I stepped on the talcum powder and left an invisible imprint on the mosaic. My idea was to stroll, almost naked. From then on, I didn’t stop doing performances to make trafficking visible.

I had never read that art could provoke social organization, but I lived it. In 2015, a friend of Flor Penachi called me – they were about to close their cause – and said, “I need us to do something big for my friend.” And we did. We did a performance called “Todos, todas, todxs somos Flor, todxs somos todxs”. It was imposing; we were one hundred and twenty performers, and it was done in five underground stations. There were several mothers of disappeared girls, and it was like a shock because they felt that someone was watching them. The next day, they put together “Mothers of Victims of Trafficking.” In other words, I experienced that “Ah, they see me” that made these mothers, who were ignored and broken by this neglect, empowered and organized.